I’ve recently been immersed in three very different books about architecture and design. It’s interesting how the right book often appears at the right time, clarifying something that’s been on your mind. That’s certainly been the case with these three. You see, we’ve been coasting along quite happily at Cloverdale but something was beginning to bother me and I couldn’t quite put my finger on it. And then these three books came along and I saw exactly what the issue was.

Let me tell you about the books.

- Tzannes edited by Paola Favaro and Robert Freestone (Thames & Hudson 2024)

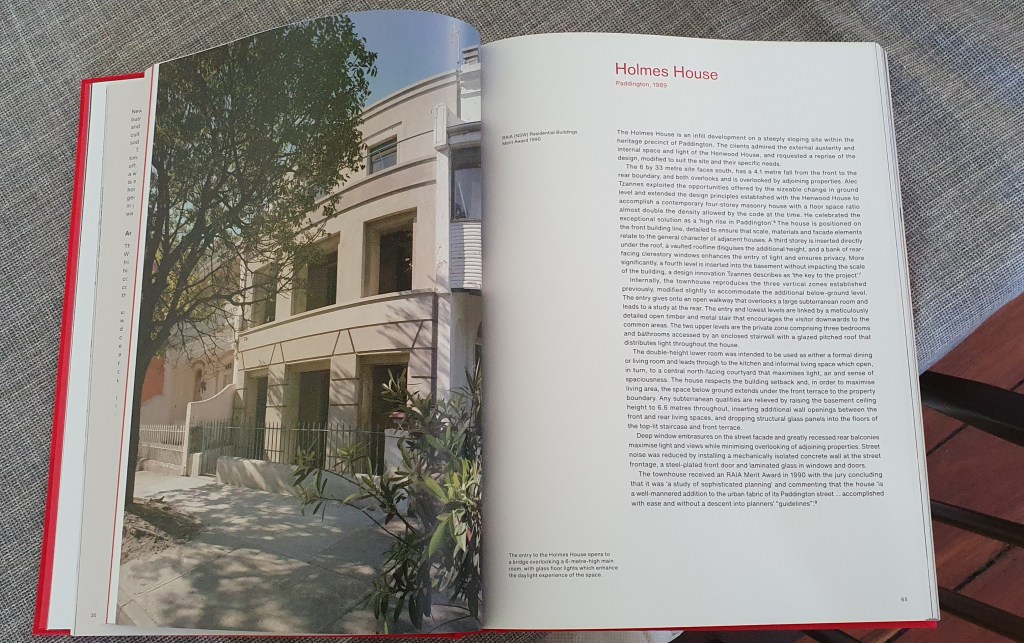

When I first arrived in Sydney in 1996, I would occasionally see a building or an addition to one and wonder who had done it. I was struck by the sense of quality, elegance, and understatement. Almost always the answer was Alec Tzannes. So I was delighted to actually spend time with him when I interviewed him for the archive of the State Library of NSW many years later (and those interviews form the basis of my chapter in this book on his young life – my only contribution). He became famous early in his career due to the Federation Pavilion in Sydney’s Centennial Park. It’s a solid little tempietto that packs a surprising punch, with an exuberantly coloured interior by Imants Tillers, and surprising elements, such as a channel of water tucked above the cornice that draws reflected light inside. His terraced houses of that period gave a svelte twist to the pretty but repetitive Victorian terraces of Paddington and Woollahra. He has worked mainly in Sydney, which means he really understands the places in which he has built. Today, his firm has completed many of Sydney’s major commercial buildings, including a couple with a structure made entirely of timber, as well of some grand harbourside houses. These projects are beautifully illustrated and accompanied by essays from notable academics, giving detail and insight on each, and exploring the language and symbols of architecture. Although it’s a lovely thing to dip into, it is a serious book, thoughtful and informative. All the work displays those qualities I first admired and a sense of fastidiousness, which is apparent even in the layout of the book itself. There is an abiding sense of integrity, not just in the use of solid materials rather than veneers or other facings but in working with the site, and respecting the surrounding buildings. It’s a beautiful monument to a life’s work (that is ongoing, I hasten to add).

- Big Garden Design by Paul Bangay (Thames & Hudson 2024)

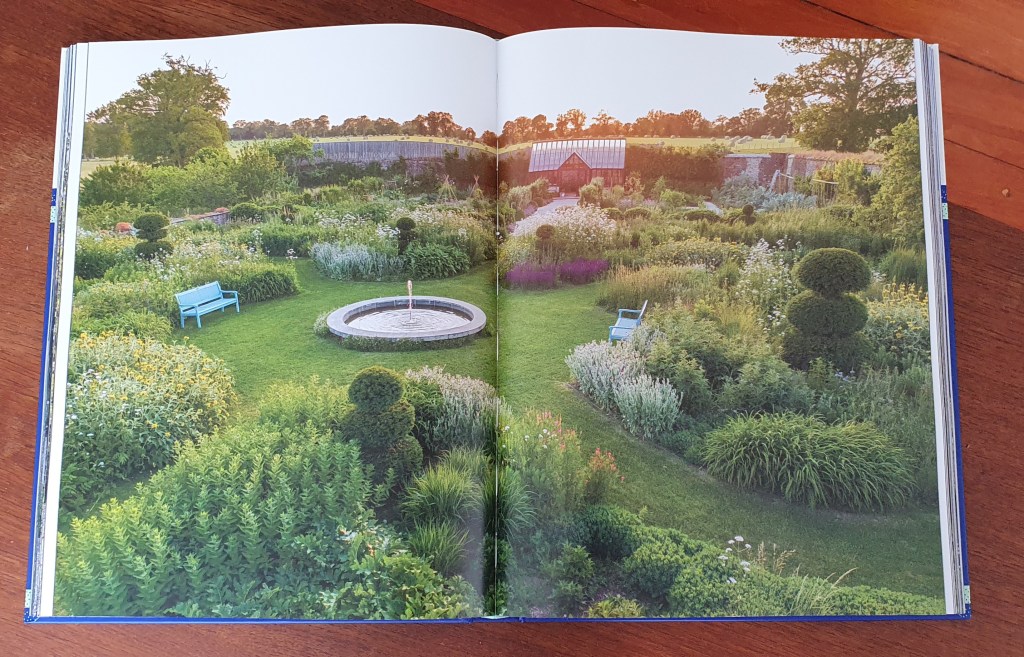

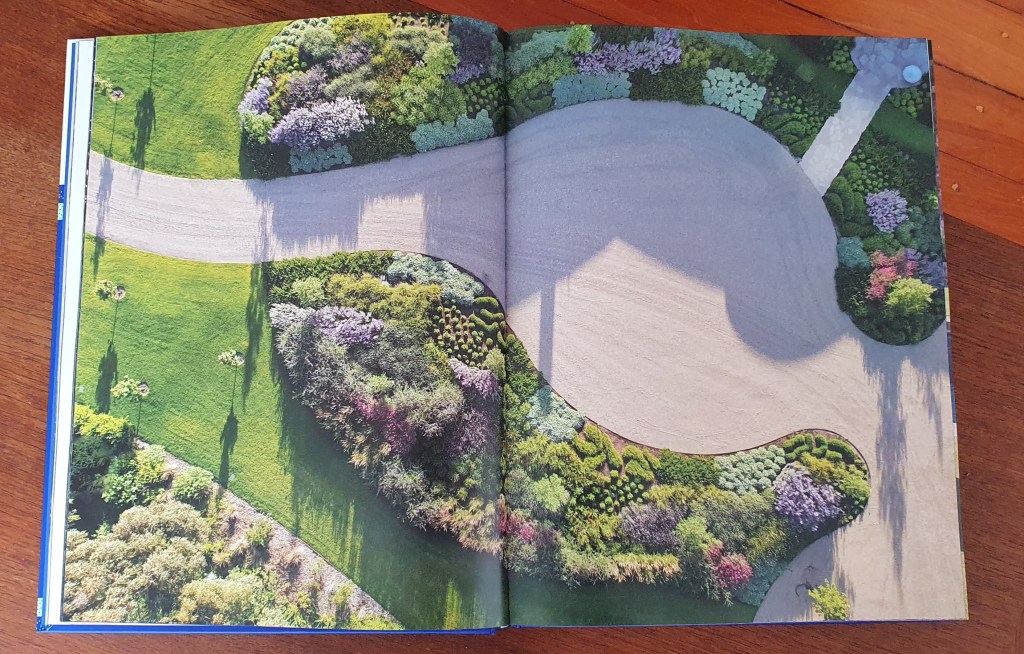

I first came across Paul Bangay in the 1990s when interiors magazines would mention that a smart inner city house had a Paul Bangay garden. This invariably meant clipped box hedges, iceberg roses and a water feature. They were smart and elegant and seemed to capture a moment when Australia was choosing to be more urbane. His work has developed since then, although there’s still plenty of clipping in his latest book, Big Garden Design. It’s a lavish exploration of many of the large gardens he has designed over the years, in Australia and elsewhere. I particularly like the drone shots which allow you to inspect the exact placement of plantings. There are grand gestures like monumental staircases and sometimes a touch of Marie-Antoinette in kitchen gardens that are more path than planting, but always there is a sense of linking the garden to the landscape and creating special places to linger, either alone or in company. Although I tend to avoid large books because they’re often too heavy and too large to hold, in this instance the size allows you to enter into the lushness of these gardens and enjoy their order and abundance.

- An English Vision by Ben Pentreath (Rizzoli 2024)

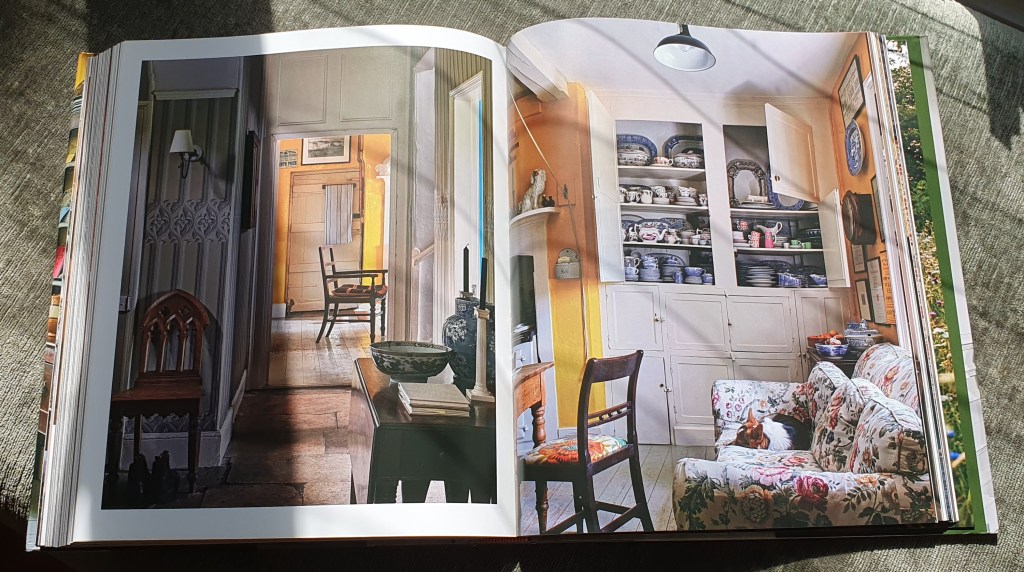

A looser style of garden is very much the province of gardener Charlie McCormick, whose husband Ben Pentreath has written a marvellous book called An English Vision. I’ve followed the pair of them on Instagram and admired (and envied, I admit) their colourfully comfortable life in an old parsonage in Dorset. Pentreath’s interiors are colourful, sometimes cluttered and always comfortable. He is also involved in several new developments, including Poundbury in Dorset, the ‘new town’ started by the-then Prince of Wales to show a more traditional way of doing things. It’s part of the traditional architecture movement which is often dismissed as pastiche, with its love for Georgian facades, ornate cupolas and fancy ironwork. I used to dismiss it, too, although I’ve never visited Poundbury, but I was still interested to read what he said about it. Like others, he contends that traditional architecture has done so much that is right so why do we need to change things? My argument has always been to question why it has to look exactly like the past, copying rather than evolving. Architects like Peter Barber, for instance, have shown the charm of the past in a fresh and contemporary way. But then, in this book, Pentreath makes the case for background architecture, the familiarity of buildings looking as we expect they should, and says that the setting is the most important thing. I’m certainly more onside with his more modest country houses in the local vernacular than the grand new mansions but at least these latter sorts have quirky details, like ping pong tables in the library. (And Pentreath did write a wonderfully scathing article in the Financial Times about ghastly clients with too much money.)

This might be a world of upholstered walls, canopy beds and pleated lampshades but it’s an inviting one. I enjoyed his obvious admiration for the Arts and Crafts, and his love of colour and fine joinery. Comfort and cosiness are words that crop up a lot. For Pentreath the pleasure is found in the detail of a door or a window seat that is wide enough for a Sunday nap. Those qualities are so often ignored in modern buildings, especially in the bog-standard housing developments of Britain and Australia. And yet they are not era-specific. They’re the things I enjoy so much in many of Le Corbusier’s buildings, for instance, especially the apartments in the Unite d’habitation in Marseille. They are apparent also in the quiet interiors of Tzannes’ buildings and in the nooks within Bangay’s gardens.

These books share a common theme, of ideas expressed with consideration and done well. They’re a call to each of us to put up with less crud and be more mindful of our spaces. To have homes (and city offices, too) that add to the streetscape and are beautiful places in which to live and work; to create gardens that amplify and enhance nature; to question the soul of the buildings in which we live. We might never upholster a room in linen but we can paint it in a colour we adore. And while our garden mightn’t have space for a parterre, a single plant in a lovely pot can give us much pleasure. It’s about the integrity of a well-considered idea and knowing what feeds us.

And that was my itch that needed to be scratched. Constancy. I realised that our desire for this home to be a special place was being dampened by normal life, when stopgap measures had become normal, and we were cluttering the place with stuff we didn’t really want. The ‘this’ll do’ syndrome that I’m prone to. These three books reminded me to aim higher and to maintain integrity in all the ways I can. Not a bad dictum for life, really.

Leave a Reply