We arrived as dusk fell. The streets from Dessau railway station were cobbled and deserted, adding an air of mystery. This was my first visit to one of the most significant buildings of the twentieth century and already I felt that I was tumbling back in time.

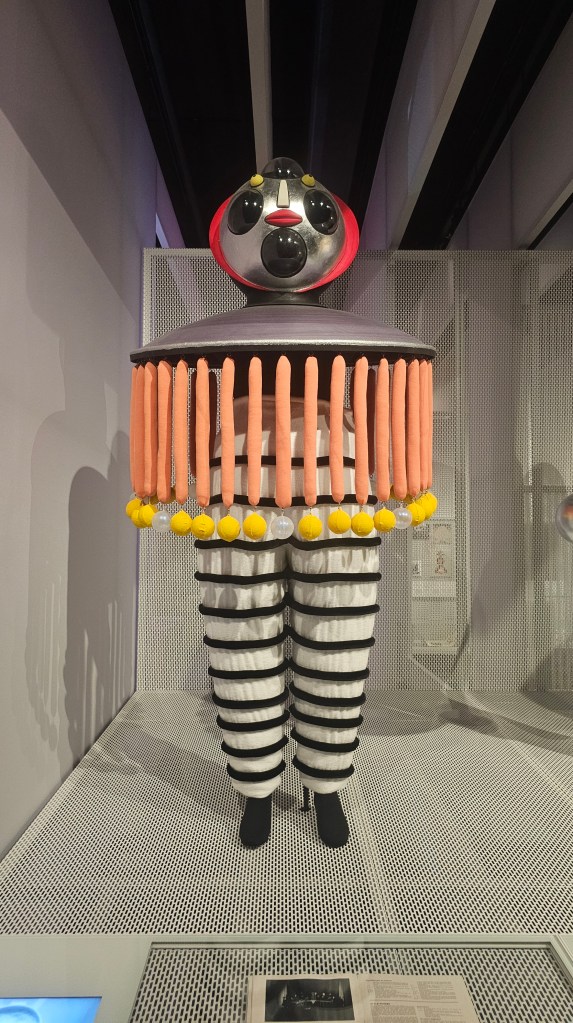

And suddenly there it was, rising up before us, its windows softly lit from within. The Prellerhaus is the student dormitory building attached to the Bauhaus teaching building. It’s famous for its jutting, iron-railing balconies on which Bauhaus students cavorted in the 1920s. They captured the youthful exuberance of the place in the 1920s, where its riotous parties, loud music and bizarre costumes were famous. Seeing them now I could almost hear the music.

The Bauhaus building at Dessau has long occupied a special place in my heart, sentimental though it is. From day one at university, when we pondered crosscurrents between music and art, to my Finals three years later, the Bauhaus and its people kept popping up. Many of my friends were enthralled by Dada, Constructivism and Surrealism but it was the architecture of the early 20th century that really grabbed me. I was fascinated by Le Corbusier’s concrete-framed houses, by Mies van der Rohe’s glass towers, and Walter Gropius’s astonishing factories with their floating staircases. The Bauhaus building brought together many of those elements, which is perhaps unsurprising, given that Corb, Mies, and Gropius all worked, briefly, for the same man, Peter Behrens, in Berlin. It was Behrens who more or less invented branding, famously designing everything for electrical company AEG, from its factory buildings to its letterhead. He was a huge influence on Gropius in particular, supporting the idea of giving equal importance to every part of design. The term gesamtkunstwerk or total work, summed it up, and the Bauhaus was all about creating it.

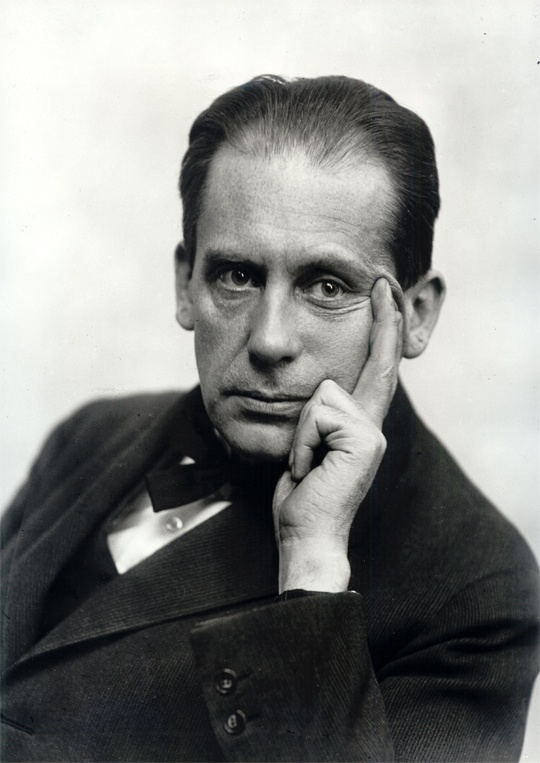

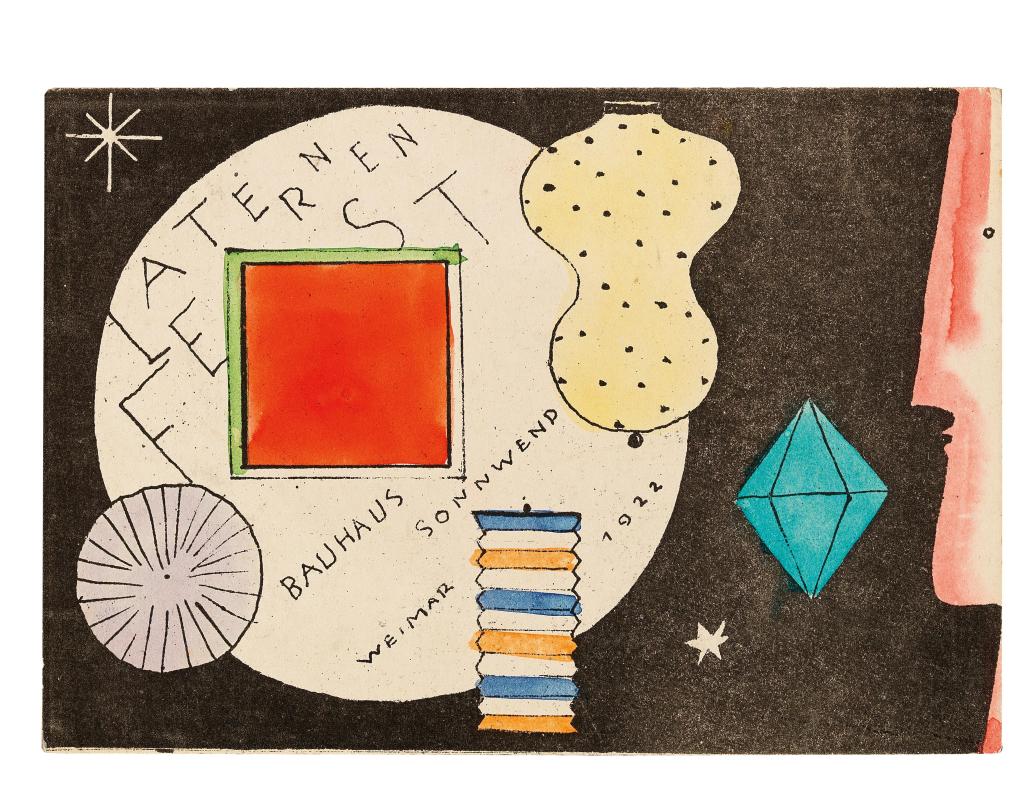

The Bauhaus started out in Weimar in 1919, just after Germany’s humiliating defeat in WW1. Gropius transformed an existing art school into a more dynamic organisation, assembling an incredible array of teachers to explore all aspects of craft and design. This was his particular strength, drawing together people of different talents.

The school in those days had a focus on traditions like weaving and metalwork and how they might be updated. Its teachers included the charismatic Swiss painter, Johannes Itten, who created a Preliminary Course that all students had to follow, in which he had developed his famous colour theory with its nuanced approach to colour. Everything was open to discussion.

When the Bauhaus began to attract negativity from local citizens, who saw its strange, cultish ways as too weird for comfort, Gropius decided it was time to move. The city of Dessau had a socially progressive mayor who welcomed the design school and made funding available. With the change of location came a change in focus, with Hungarian Laszlo Moholy-Nagy now leading courses that had a more industrial bias. Art and technology, a new unity, was its new tag.

In 1925 Gropius designed the new school, workshops and student housing, as well as several houses for the masters of each discipline, which included painters Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee. In 1926 the building opened, attracting huge attention for its cutting-edge architecture. Bauhaus objects, such as furniture, glassware and ceramics, would be sold around the world.

It is all a marvel, especially when you put it into the context. This was the time of the Paris exposition that brought Art Deco to life, with its love of veneers and streamlining. The Bauhaus was altogether more utilitarian. Along with a flat roof and a reinforced concrete frame was a vast wall of glass bringing light into the workshop wing. Gropius had already shown his love for glass in the Deutsche Werkbund model factory of 1914 and the Fagus factory of 1911.

While other architects like Le Corbusier had introduced large windows to their buildings, Gropius’ curtain wall took it to another level. (And yes, it created problems with heat and cold, as anti-modernists still like to trumpet, but this building was testing boundaries, just as the students did inside.)

An incredible bridge containing two levels of offices and classrooms links the workshop wing with the teaching wing. This extraordinary building is a hundred years old, and you can’t fail to be impressed.

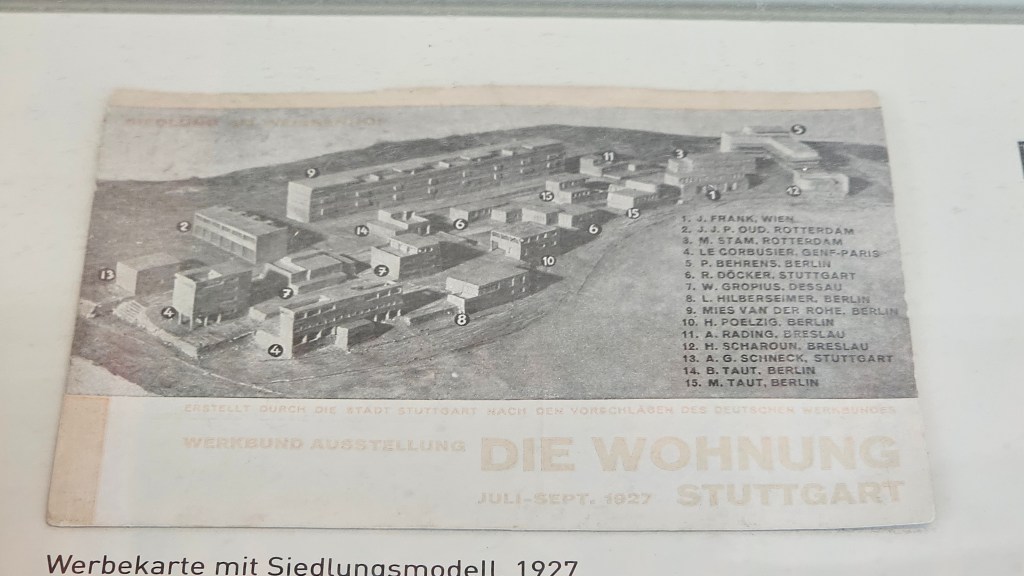

We’d started the day in Stuttgart, visiting buildings of the same period at the Weissenhof estate, a development of experimental housing, all organised by Mies van der Rohe in 1927.

It’s filled with work by leading architects, including Le Corbusier, one of whose houses is now the museum. Gropius had also designed a house but it was destroyed in WW2. The only Gropius building I’d ever seen in person was a house he designed in Chelsea in 1935 and which had been horribly mutilated, covered with black tiles, the windows changed. The Bauhaus had also been submitted to some terrible changes over time but thankfully, from the 1990s onward, it was properly restored. And now here I was, standing before it.

I have become so used to Le Corbusier’s buildings lifted off the ground on piloti that it was odd to see how the Bauhaus building hunkered into the earth. In fact, my first steps inside were downward, to the little bistro-bar that occupies the semi-basement. It was a cosy place, lit with an orangey glow, like a basement bar in a city. A few academic-looking men chatted over drinks, architects, I presumed. This was where we needed to check in.

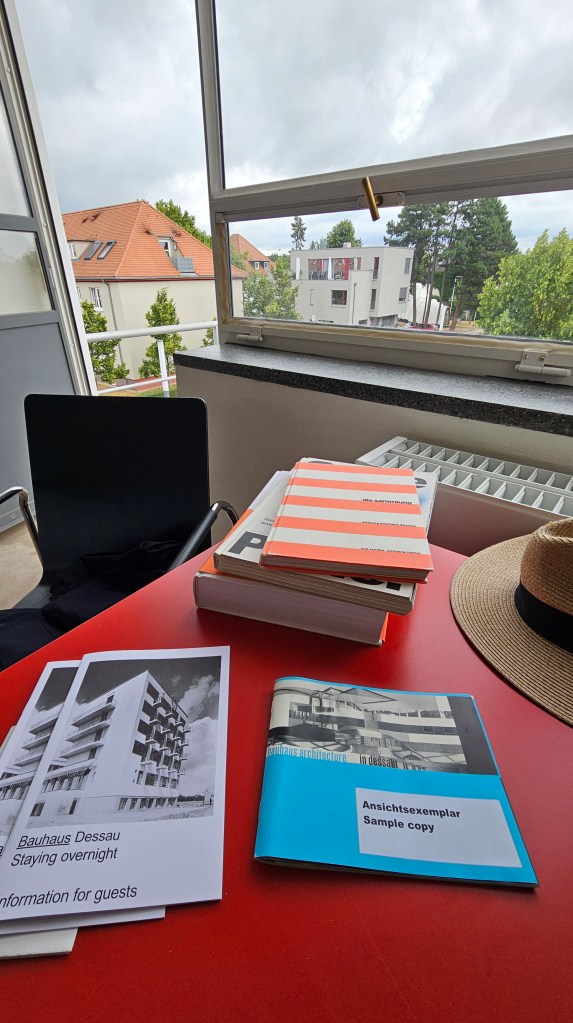

The thrill of this visit was to not merely see the building but to stay in it. It’s always a transformational experience, as I knew from having spent nights at Corb’s La Tourette and his unité d’habitation in Marseille. You experience how a space works as you use it and hear how it sounds at night . Sleeping in one of the student rooms in the Prellerhaus, I wondered what ghosts I might sense. Had Marcel Breuer or Marianne Brandt slept and worked in this space?

The room was spacious with a polished concrete floor, a large desk, and big windows that let in lots of light. The little balcony was big enough to hold a chair and I sat there for a while, simply basking in the pleasure of being there on a warm evening. I could easily imagine the Bauhaus students larking about along the corridor. I was in a hallowed space, and I slept very well.

We spent the next day exploring the whole building and then visited the Masters Houses, a short walk away and set among pine trees.

We had lunch in the Kornhaus restaurant on the river that was designed by Carl Fieger in 1929, who had been Gropius’s draughtsman since 1921. It has Art Deco glamour in the swooshing curve of his restaurant windows.

In the afternoon we picked our way through the Bauhaus Museum in the centre of Dessau which holds a lovely selection of original pieces from the Bauhaus heyday, including early Breuer chairs, woven fabrics and lots of plans and photographs of Bauhaus life.

Some of it, like the Club (or Wassily) chair by Breuer and the Barcelona chair by Lilly Reich, are so familiar that it’s a jolt to see the original pieces, now antiques. The building it occupies was a let-down, a black glass box with a heavy concrete interior, so it was wonderful to then stroll back to our room in the Prellerhaus and sit on the balcony, sipping a glass of wine as dusk fell once more.

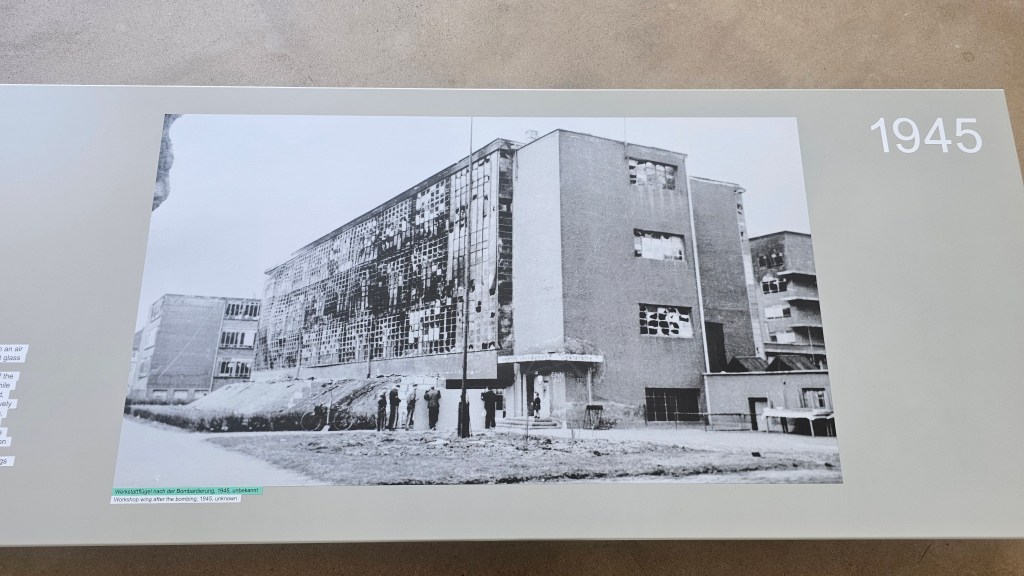

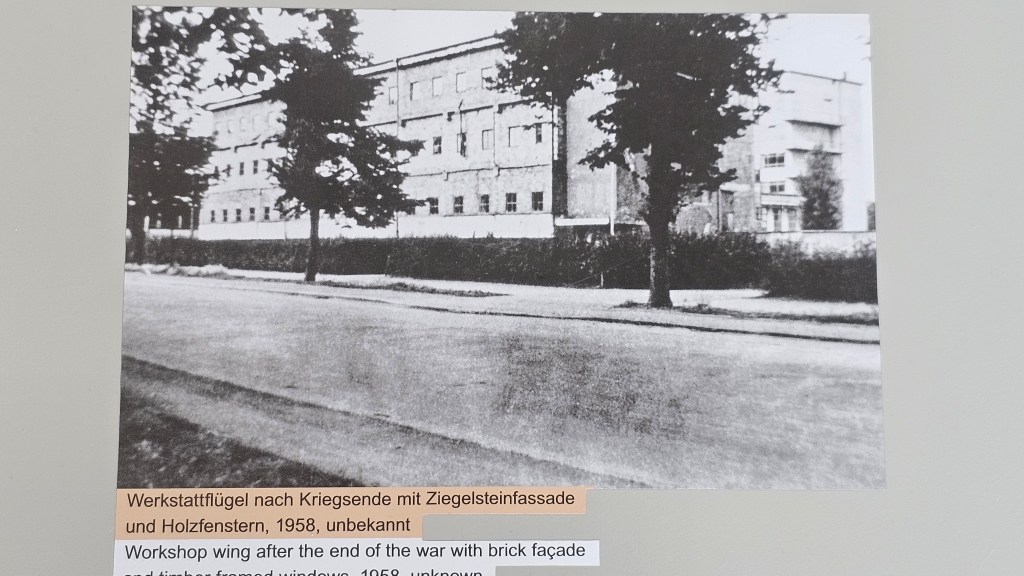

I found it incredibly moving to stay there. When I first studied the Bauhaus, Germany was divided into East and West, and travelling beyond the Iron Curtain was difficult. The building had itself suffered over the decades, being first trashed by the Nazis when the school closed in 1932 and then bombed in the war when it was used by Junkers as offices (the Junkers factory is just outside Dessau). Over time, the great glass wall was replaced by its total opposite, a solid wall with small windows punched through.

When the building was at last properly restored there were no original drawings to work off, just photographs.

Gropius went on to transform Harvard’s Graduate School of Design into a leading centre for architecture, tutoring a new generation of architects like I M Pei and Harry Seidler. Many other Bauhaus tutors and students fled to America, too, and gradually the mythic status of the Bauhaus grew. Its legacy can be seen in the way art and design is taught today, in Dieter Rams’ functional approach to design for Braun, and even in the flatpack furniture of Ikea (look at its best-selling Poang chair and you can’t fail to see the echo of Marcel Breuer’s chairs of the 1930s). Today, we accept that good design matters in all things, from teaspoons and door handles to lighting and window frames. In Gropius’s world, art was life itself. In Dessau he created a world in which everyone lived it, the spirit of an age.

I can just imagine the thrill you felt on seeing this building for real, all the more for staying within its walls. Blown away by how influential the Bauhaus design school was — so many of the modern buildings today look like pale copies.

I’m not much of a one for period drama, but if I could go back to any era it would have to be the 1920s. Will have to put Dessau on my to-visit list. Thanks for the virtual visit!

LikeLike