As an adolescent I visited the little town of Hay on Wye in the Welsh Borders with my friend Robin. We were there, with either his parents or mine, because the town was gaining a reputation. A man called Richard Booth was transforming it into a town of bookshops. It was still in its infancy but the old fire station was now a bookshop and we lingered for a long time in the biggest bookshop, which might once have been a cinema or chapel, where Booth himself was pottering with boxes of books. He reminded me of James Burke, the science reporter on BBC’s Tomorrow’s World. There were used books of every type and on every subject and Robin found an old medical tome about injuries in the First World War trenches. It was lavishly illustrated with endless photographs of men without jaws or noses, or missing whole areas of their bodies, and we were joyfully appalled by all of it until a sensible parent discovered us and snatched the book away. Booth did what he set out to do, establishing the town as a beacon for the literary world, with its book festival one of the best in the world.

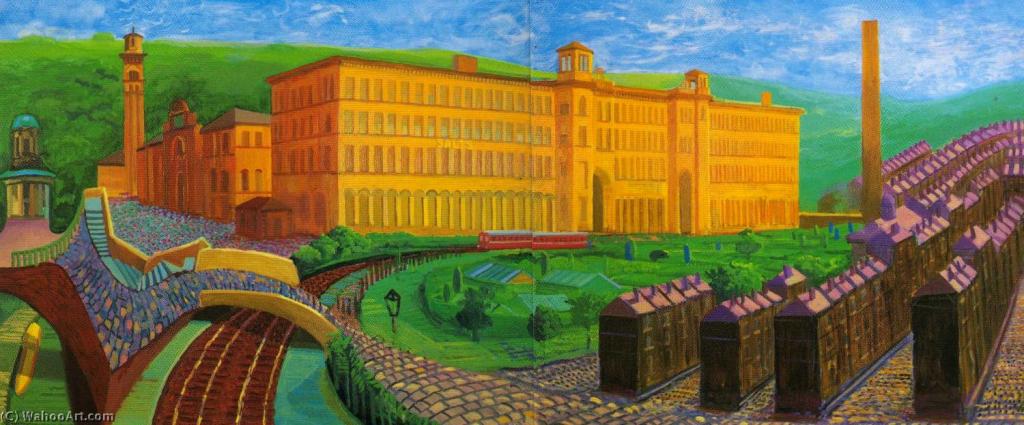

Later, but still in my teens, I visited Saltaire, a model industrial village built by Sir Titus Salt for his workers, with an elegant church and streets of pretty terraced houses close to the monumental Salts Mill. The stone behemoth with its grand towers and soaring windows was now being repurposed, its huge spaces providing studios for creatives of all types. Its owner was a young entrepreneur called Jonathan Silver who wanted to fill it with work by his friend, the artist David Hockney. One vast hall, with iron pillars and stone-flagged floors, was already hung with Hockney paintings. There were long tables piled with books on art, architecture and travel, and everywhere there were buckets and vases filled with flowers that drenched the air in scent. The whole space vibrated to the sound of a Wagner opera. It was one of the most exhilarating spaces I’d ever encountered, sensual and exciting, an encapsulation of civilisation itself. Jonathan sat quietly at a desk, delighted that we were enjoying the place. I met him again some years later, when I was working at Designers Guild, and we spent the best part of a day together, going through fabrics and furniture for his latest project, a guest house near Saltaire. I enjoyed his company immensely, a modest and highly intelligent man who was driven by a dream to create something special. It was awful to read, not many years after, that he had died from cancer at the age of 47. His vision for Saltaire continues, thanks to his daughter, and the Mill remains a stunning space, crammed with stylish design and gorgeous Hockney artworks, but missing the vital energy of Jonathan Silver himself.

I feel lucky to have worked for people who had a powerful vision. Like Christina Smith, who was instrumental in saving Covent Garden when its market was relocated and turned, with others, its narrow streets into a chic and characterful quarter of London. (I still wander down Neal Street and remember the days I spent painting the iron columns of an empty warehouse space that is now a smart store). And Tricia Guild, whose love for extravagant floral pattern and colour gave the traditionalists a run for their money. I worked, too, for David Wainwright, who travelled each year to India and beyond and brought back things that made you swoon at their craftsmanship, from stone troughs and intricate windows from Rajasthan to hand-forged iron nails from Orissa and brass railway fittings from Pakistan. I was mesmerised by these people and their apparent certainty in what they were doing. Much later in Australia, I was privileged to spend time with various architects as they recounted their memories from childhood onward for the NSW State Library archive. Sitting on the stoop of Richard Leplastrier’s deliciously simple home in the dappled light of Pittwater, north of Sydney, with the cockatoos screeching in the eucalypts and a wallaby foraging nearby, was a definite highlight, where I felt again an enormous gratitude for hearing firsthand the thoughts of a person who saw the world in a particular way. All of them visionaries, guided by beauty, who wanted to share it.

I recently read Alan Hollinghurst’s latest novel Our Evenings. As is common to all Hollinghurst’s novels, it concerns an outsider, someone witnessing a world that is often not what it seems. It’s exquisite: I don’t know another author who can make me gasp so often at the sheer rightness of a phrase or sentence. All writers seek the perfect line but most are like the classic Morecambe & Wise sketch where Eric Morecambe, making a hash of Grieg’s piano concerto as Andre Previn flinches, insists he’s playing the right notes but not necessarily in the right order. Great writing takes you into a different realm and Hollinghurst conjures for me a world that is fascinating and sometimes familiar.

A writer has a vision for their novel just as an architect has a vision for their building and its landscape, and others have a vision for how our homes might be to live in. Richard Booth’s vision for a town of books was also an attempt to combat the anonymity of global capitalism where every town looks the same and everything sold is new.

I suppose we all have a vision of some sort, however mundane, but beauty and the sharing of it is somehow fundamental. Beauty is in a fair society and a world that works as much as it is in the things we normally associate with beauty, like artwork. And I suppose I’m going down this nostalgic road because the bright beauty of the world at this moment seems clouded by greed and self-interest. Greed and self-interest can create great spectacle, even in the art world, but the vision of the people I’ve mentioned is infused with an overarching desire to share and give joy. A vision that harms no one; visions that inspire hope as well as beauty.

What brings beauty to your life?

My own house and garden work pretty well for me. I renovated a 170-year-old stone house and am now doing the garden. I have spent much more than the house is worth, but as I have no plans to sell, the pleasure the place gives me is enough. I also have the good fortune to live near Thiré, the village where the orchestra conductor William Christie has his house. His house and garden far outclass mine, as you might imagine, but he has gone farther than that. He opens the garden for annual music festivals. He is buying character houses in the village and renovating them to create housing and rehearsal spaces for musicians and singers. A once moribund commuter village is now filled with life and color. It has regained its focus. And like the places you describe it is, in its way, a form of protest.

LikeLike

The very best sort of protest, too. It’s amazing what a difference ‘outsiders’ can make not just to a local economy but to the overall atmosphere of an area. Just as I’m sure you’ve have an impact on where you live… And I totally agree about a beautiful garden. I walk around ours and watch the birds and discover strange insects and it reminds me of life going on, regardless of politics, and that nature is the most important things we have.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Beauty for me is in the creation of lovely art, great gardens, interesting furniture and objects and fresh healthy good for my and my friends enjoyment.

Buddhism.keeps my life in perspective and helps me appreciate the beauty in the world.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh yes, I agree with every bit of that, Guy. And I think the Buddhist mindset is perfect for these times. I take comfort in the Tao, knowing that everything has its season and there is a natural cycle to all of this.

LikeLike